Rescuing Pakistan’s economy

Table of contents

- I. Introduction

- II. What has gone wrong with Pakistan’s economy

- III. Corrective policies adopted but serious risks linger

- IV. A better way forward

Booming population growth and poor economic policy management have relegated Pakistan from the richest economy in South Asia to the poorest over the last fifty years. Population expansion has held back saving, investment, and economic growth. Persistent macroeconomic imbalances have resulted in an unbearably high public debt interest burden and the country faces a wall of external debt repayments coming due. Corrective policies adopted under recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs have stabilized economic conditions, as have the softening of oil prices and debt rollovers agreed to by official external creditors. Going forward, however, policy plans look tough to sustain. On the revenue side, the effort looks excessively front loaded but not ambitious enough over the medium term. At the same time, insufficient financing implies an expenditure envelope that will not permit the necessary increase in social and investment spending to meaningfully lift living standards. An alternative strategy, under which deeper tax reforms are adopted at a steadier pace and more space is given to social and investment spending, would be more promising. Policy effort and expenditures would need to focus on enhancing access to family planning, health, and education services, especially for girls and women. That would support a virtuous cycle of higher saving, investment, and economic growth over the longer term. Increased international support at concessional terms would help rescue Pakistan’s economy.1Asim M. Husain is a fellow at the Consortium for Development Policy Research and a former staff member of the International Monetary Fund. The parts of this paper relating to debt draw on and update a recent companion piece: Aasim M. Husain, “Resolving Pakistan’s Debt Problems,” Finance for Development Lab, October 22, 2024, https://findevlab.org/resolving-pakistans-debt-problems/.

I. Introduction

Pakistan’s economic performance over the past five decades was dismal. Living standards improved far more slowly than in the rest of South Asia, while expansion in access to education and healthcare also lagged. Rapid population growth—much brisker than in neighboring countries—held down saving and investment substantially, severely constraining economic growth. At the same time, poor macroeconomic policies resulted in persistent imbalances punctuated by frequent crises. The latest crisis germinated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the adoption of unaffordable budget and credit policies. The cost of servicing public debt had risen so much that it was eating up almost two-thirds of government revenue. As foreign exchange reserves were depleted and global oil prices escalated, default on external debt obligations seemed imminent as Pakistan faced a wall of annual debt repayments that far exceeded its reserves.

The adoption of corrective policies under an IMF financial support program has brought Pakistan back from the brink, but sustaining the program as currently designed will be challenging. Official creditors, who together hold the bulk of Pakistan’s external debt, have committed to rolling over principal repayments coming due, thereby addressing the near-term amortization wall. The normalization of world oil prices has also helped, dramatically reducing the import bill and allowing reserves to recover and the rupee to stabilize. However, insufficient new concessional financing has imposed an excessively harsh spending path. Pressing needs to improve education and health access for the poor and enhance climate resilience will be left unaddressed. Moreover, while plans to broaden the tax net are sound, the speed with which tax revenue is being targeted to rise is unrealistic and could prove self-defeating. In view of these risks, some observers have suggested debt restructuring as an alternative, but such a strategy would magnify, rather than mitigate, the risks.

A surer way to rescue Pakistan’s economy entails a more balanced, but also more sustained, fiscal adjustment effort coupled with strong and well-funded efforts to slow population growth and improve access to education and health services. Commitment by economic policymakers will be needed to raise revenue at a steady pace well beyond the level targeted under the IMF program, and to significantly redirect and augment spending. Far-reaching improvements must be achieved in the areas of health and education, especially for girls and women, so that the average Pakistani’s standard of living starts to catch up with that of the rest of South Asia. A better living standard is also essential to sustain the momentum for needed economic adjustment and reform. To achieve the saving and investment rates that would meaningfully lift economic growth over the longer term, population growth will have to slow markedly. With fiscal space already stretched as far as possible, such a strategy would rest on much surer footing with a sizable infusion of concessional financing from multilateral and bilateral creditors.

This paper is organized as follows. Section II starts by sketching the unfavorable past performance of the Pakistan economy, covering the relationship between Pakistan’s burgeoning population, low saving and investment, and anemic growth. It then outlines the principal macroeconomic challenges faced by the economy—the mushrooming interest bill that the government must pay on its debt and the wall of external debt repayments coming due over the next several years. Section III describes the IMF adjustment program that is now under way. It documents how the program has helped stabilize the economy but cautions that the initial pace of adjustment may prove self-defeating. Moreover, insufficient financing places the key objective—a sustained improvement in Pakistanis’ living standard—at risk. Section IV concludes by suggesting a better path under which a deeper adjustment effort is undertaken, with special attention to family planning, education, and health access to promote much greater saving, investment, and economic growth over the longer term. Increased international liquidity support on concessional terms over the near and medium term could greatly enhance the prospects for rescuing Pakistan’s economy.

II. What has gone wrong with Pakistan’s economy

Over the past half century, Pakistanis’ standard of living has declined precipitously relative to their South Asian counterparts. Galloping population growth and poor economic policy management are to blame. Population expansion has depressed saving and investment, which, in turn, has hamstrung economic growth. Meanwhile, the government has run up public debt by persistently failing to live within its means, so much so that interest on that debt now eats up almost two-thirds of public revenue and leaves little to spend on essential items. Economic policymakers’ preference to keep imports cheap—via an overvalued exchange rate while running up external debt—has made the economy uncompetitive and caused frequent crises. Foreign exchange shortages have periodically emerged, necessitating cycles of steep devaluation of the currency and adoption of painful austerity measures that have subsequently been reversed. During the latest episode in 2021–2023, foreign exchange reserves of the central bank fell to about two weeks’ worth of imports and less than one-quarter of the external public debt repayments falling due over the coming year. The rupee lost more than half of its value against the dollar and inflation jumped to 38 percent, seriously impacting the living standard of the average Pakistani.

Going from richest to poorest

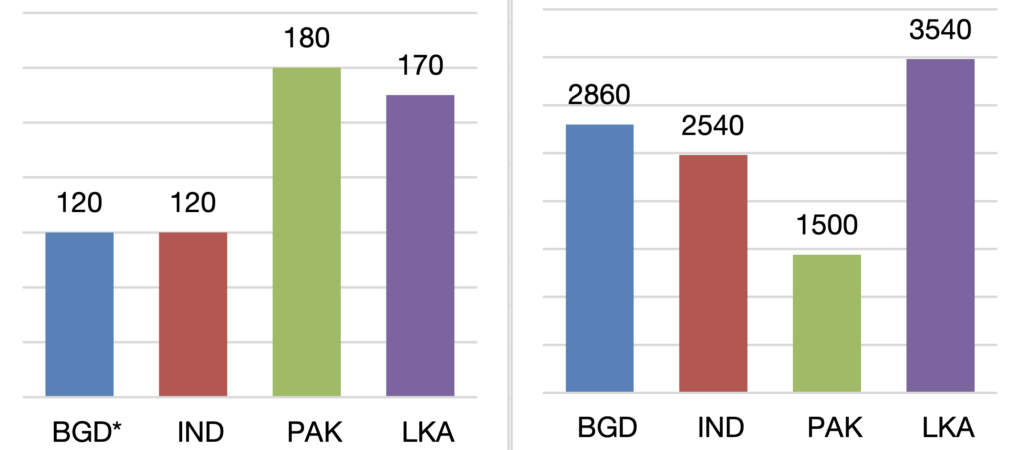

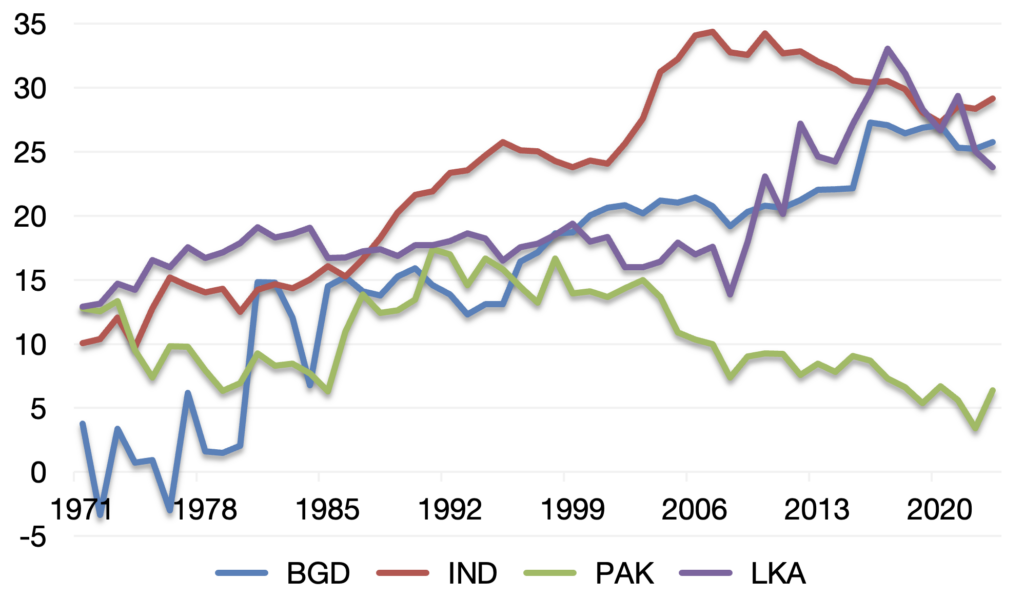

Pakistan’s economic performance over the past fifty-five years has been dreary compared with that of its neighbors, in terms of both economic well-being and socio-economic attainment. In the early 1970s, the average Pakistani’s income was higher than that of the average Sri Lankan, and almost one and a half times that of the average Bangladeshi or Indian. By 2023, Pakistan’s per capita income had fallen, in relative terms, to only about half of the level in those other three countries.

Gross national income per capita

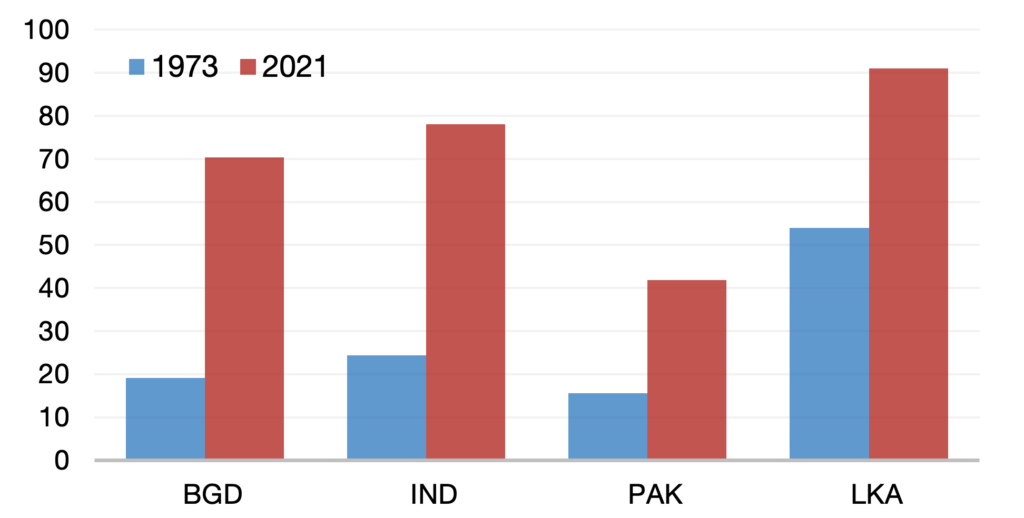

The story has been similarly disappointing in terms of health indicators. In terms of enhancing life expectancy and curbing the prevalence of stunting among children, progress has been much lower than elsewhere in South Asia, with Pakistan falling to last in each category. Educational attainment—whether measured through primary school completion rates or secondary or tertiary school enrollment—has also failed to keep up. In all metrics, Pakistan stands well behind its neighbors today, even though it was at a comparable level just a few decades ago.

Secondary school enrollment rate (percent)

Life expectancy at birth (years)

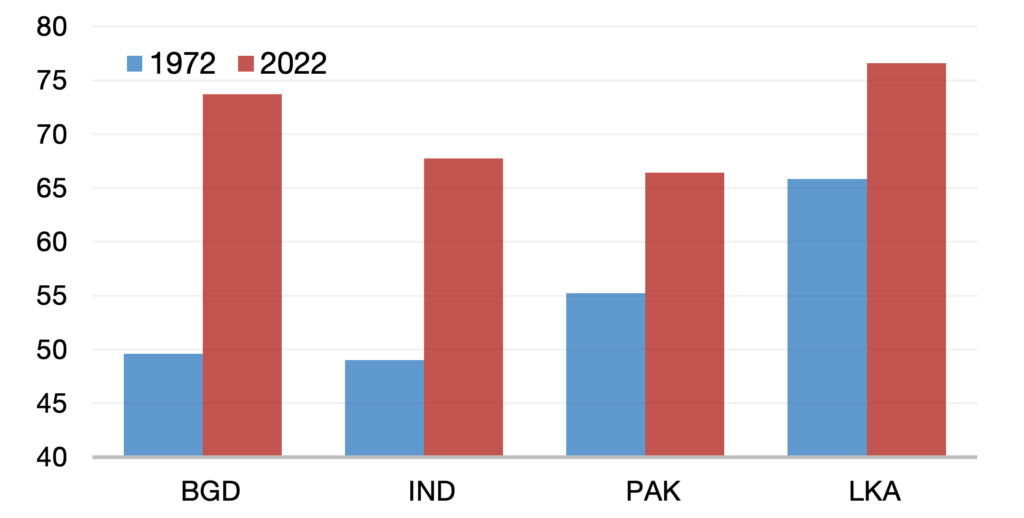

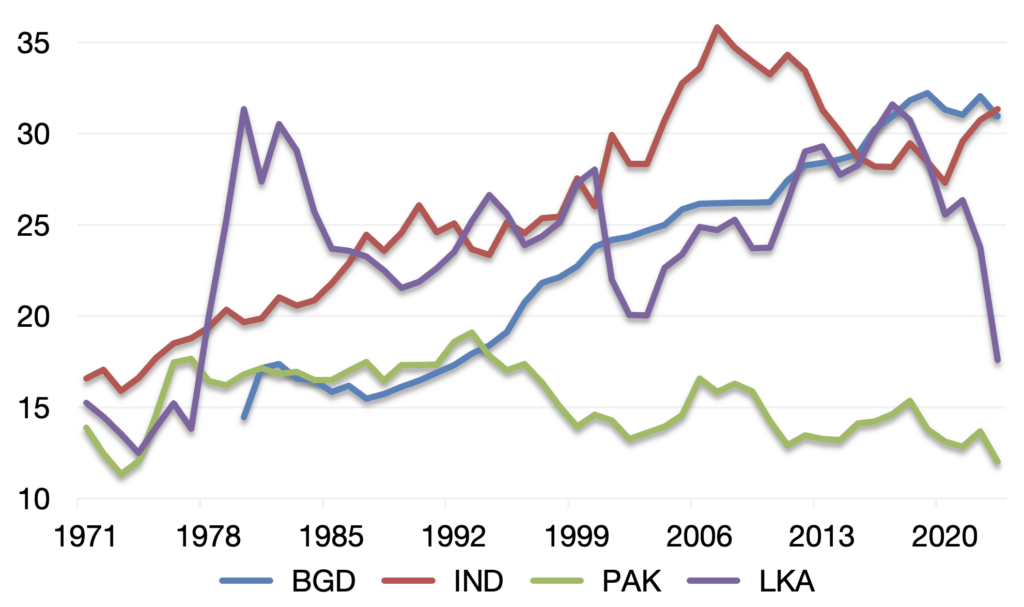

Failure to invest adequately has held back Pakistan’s economic growth and its advancement in human achievement indicators. Investment, whether in development of human resources or in building capital resources such as infrastructure, factories, or machines, expands the ability of an economy to produce more goods and services, and to produce them more efficiently. Since the 1980s, Pakistan’s investment rate (or gross fixed capital formation in relation to its gross domestic product) has been consistently lower than that of India and Sri Lanka; since the mid-1990s, it has also been much lower than that of Bangladesh. In the years before the global pandemic, Pakistan was investing less than half as much as its neighbors. In contrast to the other countries, Pakistan’s investment rate has trended downward over the past three decades. It is no surprise, then, that economic growth was weaker than elsewhere, and human development, as measured in terms of educational and health outcomes, also lagged.

Gross fixed capital formation (percent of GDP)

An inability to save constrained the availability of funds for investment. Although foreign borrowing and direct investment can supplement domestic investment, the bulk of the financing for investment in any economy comes from domestic saving. In Pakistan, the domestic saving rate has been well below its neighbors’ since the late 1990s, and the gap has widened steadily. Over the past five years, Pakistan saved at a rate that was only one-fifth as high as that of other South Asian countries. It is no wonder, then, that investment was also much lower. Many factors determine saving behavior, such as wealth, income growth, and structural factors. All have undoubtedly mattered, but the effect of population growth was especially significant.

Gross domestic saving (percent of GDP)

A key reason why saving is so meager is that a much larger share of Pakistan’s population isn’t of working age. To see how that affects saving, consider the saving behavior of two typical households. If they are identical in terms of income, wealth, and other factors, and differ only in their number of young children (who are not of working age), the household with fewer dependents will clearly be able to save a greater fraction of its income. This difference has been stark in South Asia. Pakistan’s ratio of working-age population to total population is presently below 60 percent, while other regional countries reached that level in the 1980s (Sri Lanka) or the 1990s (India and Bangladesh) and now have ratios at or above two-thirds.

Working age population (percent of total population)

Pakistan’s rapid population growth has kept its working-age ratio low, which inhibits saving. In fifty years, the number of Pakistanis has quadrupled while the number of Sri Lankans has less than doubled and the populations of Bangladesh and India have increased two and a half fold. Hence, the share of young people has remained much higher in Pakistan while it declined rapidly in the other countries. In 2023, 36 percent of Pakistan’s population was fifteen years old or younger, compared to 22–25 percent in Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka. This translated into relatively fewer working-age people who could save and more dependents on whom their income had to be spent.

Policy mismanagement

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s persistently large fiscal and external deficits have resulted in a rapid rise in public debt and in the interest cost to service that debt, as well as frequent shortages of foreign exchange and repeated economic crises.2The fiscal deficit refers to the government’s budget deficit. The external deficit refers to the deficit in the current account of the balance of payments. The latest crisis took root in the aftermath of the global pandemic and came to the fore after the commodity price shocks precipitated by the Russia-Ukraine war. Unaffordable policies such as heavily subsidized credit schemes introduced by the central bank and expanded government spending, especially bigger energy subsidies, amplified the already large external and fiscal imbalances. By the end of fiscal year 2021–2022 (July–June), the budget deficit had widened to almost 8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and the external current account deficit to near 5 percent of GDP. Reserves were plummeting and imports were surging. The crisis forced policymakers to impose controls on imports and allow the rupee to depreciate. In two years, the value of the rupee fell by more than half against the dollar, sharply raising the value of external debt in rupees and increasing its share in total public debt. As of mid-2024, public and publicly guaranteed debt amounted to 75 percent of GDP, of which around 40 percent was denominated in foreign currencies and owed to external creditors.

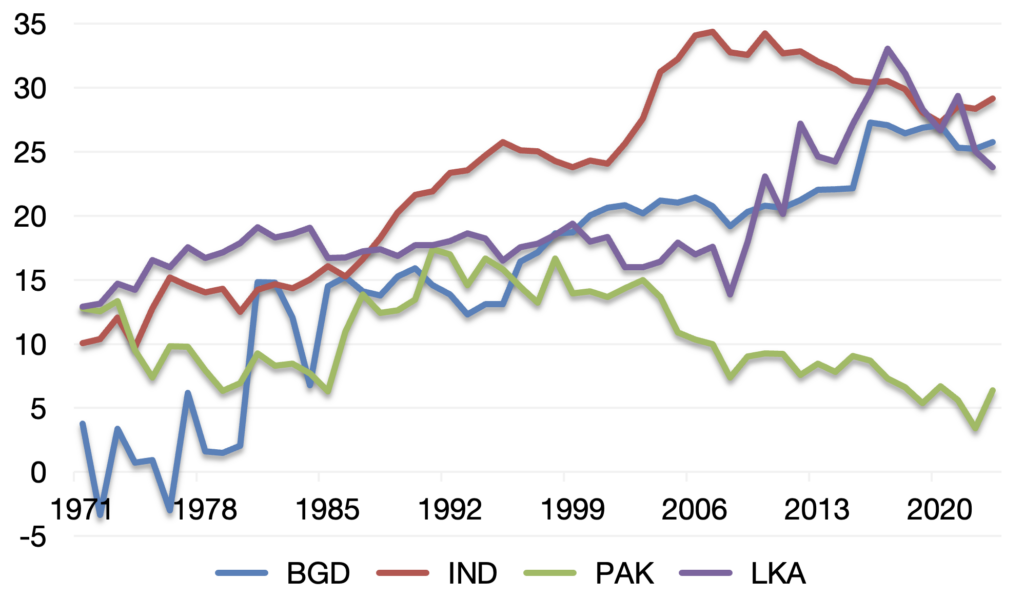

1. The hefty interest burden

The persistent failure to generate revenue sufficient to meet expenditure requirements has long plagued Pakistan. Consistent fiscal gaps over the years have led to an accumulation of public debt, which by the end of 2018–2019 amounted to almost 80 percent of GDP, approximately seven times the government’s annual revenue intake. That year, the final one before the onset of the pandemic, government expenditures surpassed revenue by an astounding two-thirds. Both ratios, relative to revenue, ranked among the highest in emerging market and developing economies worldwide. The perpetually large public-sector deficit has also swallowed up much of the banking system’s financing, thereby crowding out private investment.

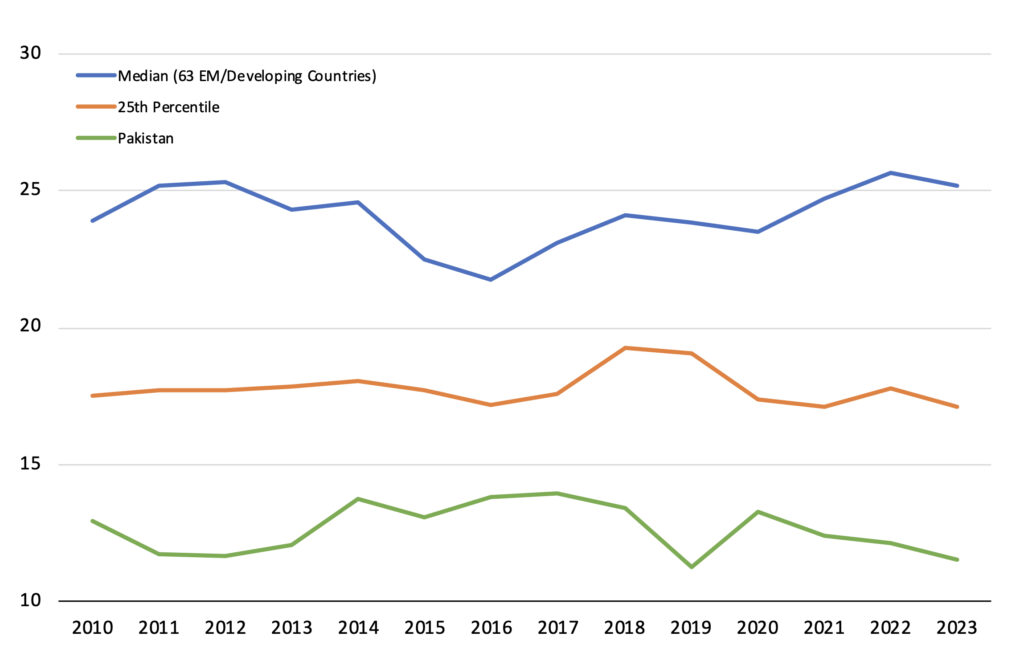

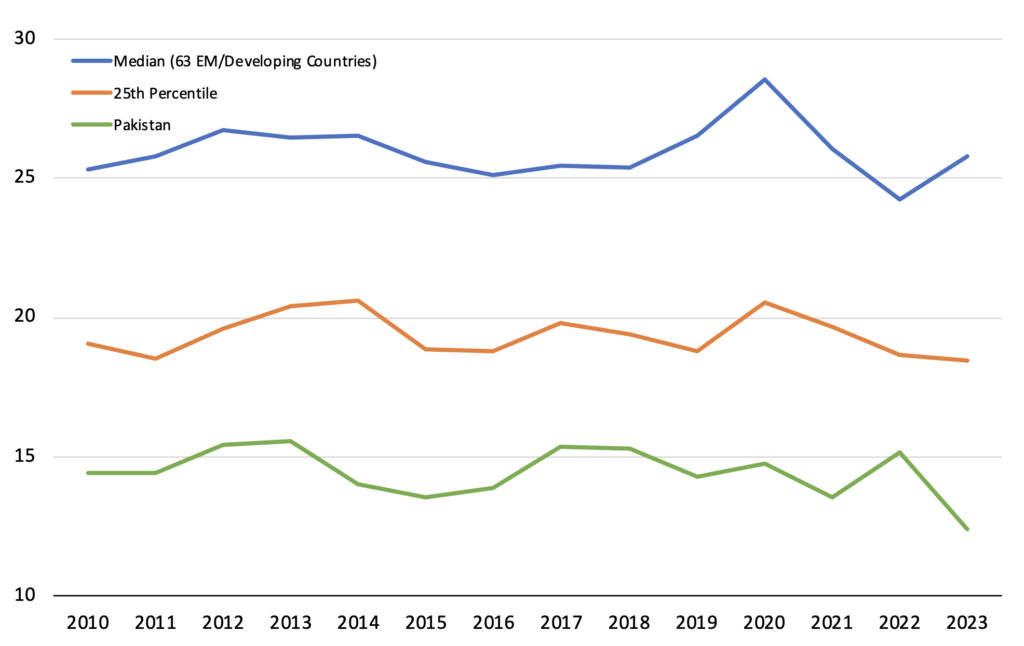

As debt continued to climb, so did the interest payments that the government was obligated to make. By 2018–2019, these payments consumed more than 40 percent of the government’s annual revenue intake. Put differently, nearly half of the government’s earnings were being funneled into servicing interest to pay for past spending, significantly constraining its ability to meet present expenditure requirements without resorting to even more borrowing. Historical patterns from other countries indicate that maintaining a ratio above 25 percent for a prolonged period is uncommon. Indeed, in the decade leading up to the global pandemic, Pakistan was one of only five emerging markets or developing economies, out of a sample of more than sixty countries, that saw this ratio reach or exceed 40 percent. Only one other country ever even reached 30 percent, and only three others went beyond 25 percent during 2010–2019. Thus, international experience suggests that it is important not to let the interest-revenue ratio rise above 25 percent. By contrast, in Pakistan in the last two years—following the onset of the latest economic crisis and the escalation in borrowing costs—this ratio has reached 60 percent, again one of the highest among all countries. This is clearly unsustainable, both fiscally and from a social stability perspective.

Public interest bill (percent of government revenue; 2023)

2. The external debt repayments problem

In an effort to keep imports relatively cheap, Pakistani policymakers have tried to sustain an overvalued rupee by borrowing foreign exchange rather than earning it. Traditionally, the foreign borrowing came mainly through aid inflows but, increasingly, Pakistan has turned to commercial borrowing.3See, for example: Saqib Jafarey, et al., “Are Overseas Remittances a Source of Dutch Disease in Pakistan?” Consortium for Development Policy Research and Finance for Development Lab, Paris School of Economics, March 2024, https://cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Policy-Brief-3-1-Overseas-Remittances.pdf. They conclude that high inflows of aid and remittances helped sustain exchange rate overvaluation, which, in turn, held back export growth. However, whenever oil prices have spiked (energy imports account for 20–40 percent of total imports), aid flows have declined, or access to international borrowing has dried up, the perpetually low official reserves cover has eroded to dangerous levels. This has precipitated rupee devaluation, a collapse in economic growth, and signing on to an IMF program to gain access to exceptional financing.

In the latest episode, in fiscal year 2021–2022, the story was similar but magnified. Stepped up external borrowing, a temporary reprieve on account of rich countries’ debt service suspension initiative (DSSI, which suspended $3.7 billion of debt service payments), and exceptional financing from the IMF during the pandemic ($1.4 billion emergency financing plus $2.8 billion special drawing rights allocation) provided the foreign exchange for an external shopping spree. Massive, subsidized credit schemes launched by the central bank further fueled import demand. The external current account deficit widened to nearly 5 percent of GDP, reserves fell rapidly, and import growth reached 60 percent on an annual basis during part of the year.

Then came the moment of reckoning. The DSSI concluded and access to international market financing evaporated. New bilateral and multilateral lending also slowed. The commodity price shocks triggered by the Russia-Ukraine war compounded the problem by driving up the cost of imports, particularly oil, even higher. Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves plummeted further, while private external financing became virtually inaccessible. By June 2023, reserves had dwindled to less than $4 billion, barely enough to cover two weeks’ worth of imports and only 10 percent of the staggering $30-billion gross financing needs for the coming year. With such meager reserves and external debt repayments of $15–20 billion in each of the next five years looming, the external financing situation appeared untenable. Drastic import restrictions had to be enforced to contain the crisis, and interest rates were hiked sharply. These measures, however, severely disrupted economic activity. By the end of 2022–2023, the rupee had lost more than half its value against the dollar in just two years and inflation shot up to 38 percent.

III. Corrective policies adopted but serious risks linger

Macroeconomic conditions have started to improve since mid-2023, after corrective policies were adopted and an adjustment program was agreed upon with the IMF. Bilateral and multilateral creditors—who together hold around 85 percent of Pakistan’s external debt—committed to rolling over principal repayments coming due, thereby addressing the near-term amortization problem. The normalization of world prices of primary commodities, particularly petroleum, also helped. As a result, official foreign exchange reserves have rebounded to above $12 billion and import restrictions have been lifted. Pressure on the rupee has subsided and the exchange rate against the dollar has stabilized. Inflation has come down to under 3 percent as of January 2025.

Paltry new concessional financing from official creditors, however, looks set to impose an excessively harsh spending path that will be challenging to sustain. Pressing needs to improve education and health access for the poor and to enhance climate resilience will be left unaddressed. Moreover, while plans to broaden the tax net are sound, the speed with which tax revenue is being targeted to rise is unrealistic and could prove self-defeating. Insufficient concessional external liquidity will also force more domestic borrowing by the government, implying a higher interest bill and greater crowding out of private investment. In view of these risks, some observers have suggested debt default and restructuring as an alternative to consider, but such a strategy would magnify, rather than mitigate, risks.

Addressing the imbalances

The latest adjustment program seeks to address the fiscal imbalance by reducing the need to borrow. Under the thirty-seven-month IMF Enhanced Fund Facility (EFF) program agreed to in September 2024, the plan is to cut the budget deficit by 3 percent of GDP (almost in half) over three years. All of this would come from increased tax revenue, with two-thirds of the targeted gain coming in the first year. At the same time, the wall of external debt repayments by the public sector, of around $14 billion annually in each of the next five years, will be overcome by getting bilateral and multilateral creditors to roll over their loans.4The IMF projects Pakistan’s external financing requirement over the next five years, including repayments to the IMF, to average around $22 billion annually. Of this, $14 billion is public debt amortization. Obtaining assurances that sound macroeconomic policies are being implemented under the IMF program, these official creditors would be expected to maintain their loan exposures to Pakistan.

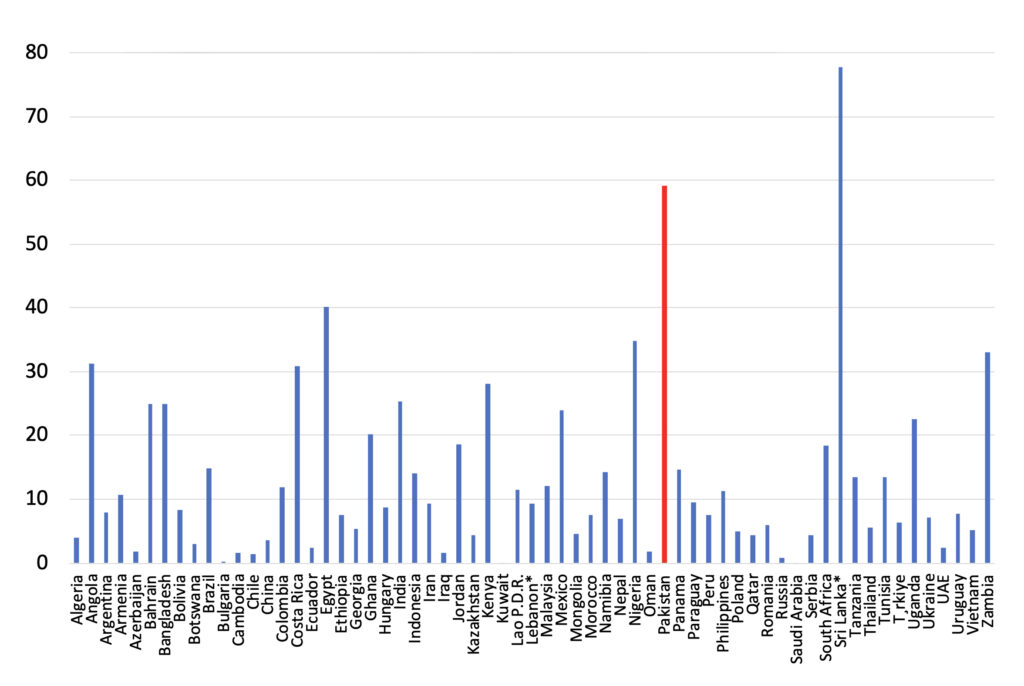

Achieving a revenue increase of this scale, by 3 percentage points of GDP in three years, looks attainable. With revenue collection currently at roughly 12.5 percent of GDP, Pakistan ranks among the weakest countries globally in this regard. As of 2021, only one out of every one hundred Pakistanis actively filed a personal income tax return. Meanwhile, the retail and agricultural sectors constitute nearly half of the economy but contribute almost nothing in income taxes. Property tax collection and tax receipts from real estate and construction services remain meager. A determined and sustained effort to expand the tax base to encompass these and other undertaxed sectors could significantly enhance government revenue. Reforming federal-provincial fiscal arrangements to provide provinces with stronger incentives to generate revenue would further support this objective. Given these factors, aiming to bridge half of the revenue shortfall (around 3 percentage points of GDP) by reaching the 25th percentile among emerging market and developing economies within three years is a reasonable target.

Revenue/GDP (percentage)

What could possibly go wrong?

While the planned tax increase over three years looks reasonable, packing two-thirds of it into the first year does not. Setting an overambitious initial target and then failing to meet it—possibly by a large margin—would undermine the credibility of the longer-term plan. On the other hand, if such a large jump in tax collection is somehow achieved, it would impart a large contractionary impulse on the economy just as it emerges from crisis. Either way, this would further magnify risks to sustaining the adjustment.

Despite the gargantuan tax effort, the space for increased primary (non-interest) spending under the program is nonexistent. The plan calls for holding primary spending at just above 13 percent of GDP for three years. Although slightly higher than the crisis-compressed level in the past two years, this would be below what was seen in each of the previous ten.5Primary spending in 2023–2024 (not shown in the chart) fell further to 11.6 percent of GDP, from 12.4 percent in 2022–2023. Moreover, despite the substantial closing of the revenue gap, Pakistan’s primary spending gap with the lowest quartile among all emerging market and developing economies of 6 percentage points of GDP would not close at all. Improving the quality of public spending is clearly necessary and will allow some increased allocation to priority areas. For example, more than 1 percent of GDP is expended on untargeted subsidies, and inefficient state-owned enterprises also devour large fiscal resources. Achieving cost savings in these areas is crucial. However, given the alarmingly high poverty rate, the dismal state of health and education—particularly for the underprivileged—and the pressing need for extensive climate-resilient infrastructure to sustain economic growth, merely reallocating these cost savings will not suffice. More needs to be spent. Without that, it is hard to see how public support for the critical broadening of the tax net can be sustained.

Primary spending/GDP (percentage)

Moreover, insufficient concessional financing will keep the interest bill excessively high and crowd out private investment. With official creditors only maintaining their exposure, rather than providing additional financing, the government’s new borrowing will need to come entirely from the domestic market at non-concessional interest rates. That will put upward pressure on domestic rates and eat into the financing available for private investment. The EFF program projects the government’s interest bill to remain above 30 percent of revenue even after five years of severe austerity, implying persistently high sustainability risk based on international experience. Investment is projected to remain weak, averaging only 15.5 percent of GDP over the next five years—about the same as in the decade before the pandemic, and below the 16-percent average level since 1990.

Modest investment and subdued overall primary spending do not bode well. Prospects for a meaningful improvement in social indicators appear dim. Space to address poverty reduction and climate resilience seems absent. Hence, Pakistan’s economic fortune is likely to remain hostage to heightened social stability and economic underperformance risks.

Debt default would make things worse

Recognizing these risks, some observers have suggested pursuing a different strategy under which Pakistan seeks to restructure its debt to free up resources to support the economy.6See, for example: Murtaza Syed, “Break the Taboos Propping Up Unsustainable Debt,” Economist, August 28, 2024, https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2024/08/28/break-the-taboos-propping-up-unsustainable-debt-pleads-a-former-central-banker; Sanjay Kathuria, “Pakistan Should Restructure its Debt Now,” Project Syndicate, September 25, 2024, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/pakistan-needs-public-debt-restructuring-by-sanjay-kathuria-1-2024-09. At the height of the recent crisis, it appeared unavoidable that Pakistan would join the growing list of heavily indebted emerging market and developing economies forced to default and restructure their debt. However, the composition of Pakistan’s debt—with almost all interest payments going to domestic creditors and virtually all of the remaining external debt owed to bilateral and multilateral creditors—severely limits the potential benefits from default or restructuring, while imposing considerable costs.7See, for example: Aasim M. Husain, “The Right Medicine for Pakistan’s Ailing Economy,” Project Syndicate, December 16, 2024, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/how-to-address-pakistan-debt-crisis-by-aasim-m-husain-2024-12. In addition, Riaz Riazuddin and Sajjad Zaheer, “A Narrow Path Out of a Dangerous Place: Debt Management and Sustainability Issues in Pakistan,” Consortium for Development Policy Research and Finance for Development Lab, Paris School of Economics, July 2023, https://cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Policy-Brief-3-2-A-Narrow-Path.pdf, conclude based on more thorough analysis that Pakistan can avoid debt restructuring but will remain dependent on bilateral creditors for liquidity support.

Restructuring external debt would do little to alleviate the overwhelming interest burden and could introduce additional challenges. More than 85 percent of the interest the government pays comes from its domestic debt, meaning that, even if external debt interest payments were suspended, the overall burden would remain largely unchanged. Furthermore, defaulting on external debt would come at a steep cost, potentially disrupting trade by cutting off trade credits and exposing foreign assets to seizure by creditors seeking repayment. Given that the vast majority of external debt is owed to official creditors, failing to meet these obligations could also strain diplomatic relations with allied nations and jeopardize access to funding and development projects from multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Restructuring domestic debt could significantly reduce interest payments, but the resulting economic and financial upheaval would likely outweigh any benefits. Nearly 60 percent of the government’s domestic debt is held by banks, and these government securities account for roughly 60 percent of total bank assets. Consequently, any restructuring of the government’s domestic debt would inevitably affect bank-held debt, and any reduction in its value would directly affect the financial sector’s stability. Even a modest 10-percent haircut would wipe out the capital base of the banking system, though individual banks would experience varying degrees of impact. The resulting disruptions would be severe, affecting bank shareholders, depositors, and other government debt holders, including households and insurance and pension funds. Given these risks, restructuring domestic debt should be considered only as a last resort.

IV. A better way forward

A less risky and less painful way to rescue Pakistan’s economy is possible. It will require sustained commitment by Pakistan’s economic policymakers to not only raise revenue at a steady pace but also significantly redirect and augment spending. Far-reaching improvements must be achieved in the areas of health, education, and climate resilience, so that the average Pakistani’s—and especially poor Pakistanis’—standard of living starts to catch up with that of the rest of South Asia. A better living standard is also essential to sustain the momentum for needed economic adjustment and reform. Significantly higher saving and investment can be attained with slower population growth, which, in turn, will lift the growth potential of the economy. However, with fiscal space already stretched as far as possible, and the government’s financing need already crowding out funds for private investment, such a strategy is possible only with a sizable infusion of concessional financing from multilateral and bilateral creditors.

Getting revenue and spending right—an alternate strategy

There is no escaping the need to collect more tax revenue. Remaining among the worst-performing countries worldwide in terms of tax collection is untenable if Pakistan’s economic fortunes are to be improved. Broadening the tax net to cover those paying little or no taxes must be the top priority. Tax administration can, and should, be improved as well. Thus, the EFF program target of 3 percent of GDP revenue increase in three years is not only achievable but needs to be surpassed. Over five to six years, it should be feasible to expand revenue by a further 3 percentage points to reach the 25th percentile of emerging market and developing economies. Without that, there simply would not be sufficient fiscal space. That said, attempting to front-load the revenue effort undermines its credibility and could prove self-defeating. Targeting a steady increase of 1 percentage point a year would be much likelier to succeed.

Spending more wisely is clearly warranted, but the yawning gaps in the social services and infrastructure areas indicate that more needs to be spent in total. Allocating half of the revenue increase to primary expenditure would strike a reasonable balance between deficit reduction and advancing economic well-being. In other words, the targeted expansion in tax revenue should permit an increase in primary spending of 3 percent of GDP over five to six years. In addition, with deficit reduction the government’s borrowing need will diminish, allowing interest rates—which are already on a downward trajectory thanks to moderating inflation—to come down further.8The central bank started lowering its key policy rate from 22 percent in June 2024, once inflation had moderated significantly. Policy rate cuts have continued as the disinflation process proceeds; as of January 2025, the policy rate stood at 12 percent. As a result, an additional 3 percent of GDP in primary expenditure expansion should be attainable from savings on interest payments.9The EFF program also projects the interest bill to decline by 3 percentage points to 4.8 percent of GDP over five years. “Pakistan: 2024 Article IV Consultation and Request for an Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Pakistan,” International Monetary Fund, October 2024, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2024/310/002.2024.issue-310-en.xml?cid=556152-com-dsp-crossref. In total, primary spending would rise by 6 percentage points, bringing Pakistan to the 25th percentile of emerging market and developing economies, commensurate with the revenue side.

Comprehensive structural reforms must go hand in hand with fiscal adjustment. Beyond expanding the tax base and redefining federal-provincial fiscal responsibilities, significant strides are needed to tackle the cost inefficiencies in the power sector, in order to halt the accumulation of massive arrears while providing some relief to consumers.10Ibid. Power-sector payment arrears amounted to 4 percent of GDP at the end of 2023–2024. The arrears have accumulated because of the failure of tariffs to keep pace with prices; inefficient management of electricity distribution and transmission; under-collections from customers; and delayed maintenance coupled with weak transmission and distribution infrastructure. At the same time, both the quality and scale of social-sector expenditures—covering health, education, population planning, and income support—must be strengthened. Delegating these expenditures to provincial and sub-provincial authorities, with appropriate oversight, could enhance spending efficiency and potentially foster greater public acceptance of fiscal reforms. Additionally, such measures would help correct the unsustainable fiscal imbalance between the federal and provincial governments, in which nearly 60 percent of federal tax receipts are transferred to the provinces. Equally crucial is the privatization of inefficient state-owned enterprises, which would relieve pressure on the national budget and improve service delivery.

Changing the financing mix

However, the interest bill will only come down to a safe level with significant new concessional financing. The tax and primary spending paths described above would imply somewhat more gradual narrowing of the budget deficit than that targeted under the EFF. Government debt would still decline substantially in relation to GDP, but again a bit more gradually than under the EFF. Thus, the interest bill will also decline more slowly. Despite higher revenue under this alternate strategy, the interest-to-revenue ratio would ease to less than 25 percent by the end of the decade only if a sizable chunk of the government’s new borrowing during the next five to six years can be raised on concessional terms.

Arranging the requisite concessional financing might not be as difficult as it seems. Bilateral and multilateral lenders have already recognized the need to roll over their loans in a coordinated manner under the EFF program. In its regular reviews of the program, the IMF will seek assurances from each of the main official creditors that the rollovers will continue. Extending this coordination role to pressing official creditors to temporarily increase (rather than just maintain) exposures seems feasible. If each creditor can be assured that all others will follow suit, such coordination can be in the creditors’ collective interest because it will improve the prospect of Pakistan successfully overcoming its debt challenges. Increased data transparency relating to official creditors’ claims and effective interest rates would facilitate such coordination.11Husain, “Resolving Pakistan’s Debt Problems.”

Concessional financing should be directed toward infrastructure and climate resilience initiatives to maximize its contribution to economic growth and job creation. A portion of external funding could even be allocated to retiring, at a discount, high-emission energy projects that have become uncompetitive compared to clean solar alternatives but are still operating in order to cover debt service costs. Given the historically weak performance of public investment projects, active participation from bilateral and multilateral creditors in selecting and executing these projects appears crucial to ensuring their effectiveness.12Farrukh Iqbal and Ijaz Nabi, “Pakistan’s External Debt Dilemma,” Center for Global Development, March 11, 2024, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/pakistans-external-debt-dilemma; Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) and Finance for Development Lab (FDL), Paris School of Economics, 2024. These authors found that the World Bank’s switch to quick-disbursing budget support rather than project loans in Pakistan was associated with real exchange rate appreciation and stagnation of manufacturing and exports.

Boosting saving and investment through demographic change

Even with the requisite new concessional financing flows, the boost to investment will not be enough to close the income gap with the rest of South Asia. Official creditors’ support, in the form of well-selected and monitored investment projects, will certainly lift economic growth prospects. By reducing the government’s domestic borrowing need, the liquidity support will also crowd in private investment. As a result, investment could rise to 20 percent of GDP by the end of the decade, significantly higher than the 16.5 percent projected under the EFF program. However, the gap with investment rates in India and Bangladesh would remain large—near 10 percentage points—implying little prospect for even maintaining, let alone closing, the gap in living standards. To close the income gap, Pakistan’s investment rate must be lifted much higher. That will require much more saving, which, in turn, will depend on success in changing Pakistan’s demographic structure.

Pakistan’s saving rate would have been substantially greater if its working-age population ratio had been as high as in other South Asian countries. Economists studying the determinants of saving behavior across different countries have generally found a significant impact of changes in demographic structure on saving. Applying estimates obtained for Southeast Asian countries, it turns out that if Pakistan’s working-age ratio had been equal to the average of Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka—or about 8 percentage points more than it was over the past twenty-five years—the saving rate in Pakistan would have been almost 10 percentage points of GDP higher.13Hamid Faruqee and Aasim M. Husain, “Saving Trends in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Country Analysis,” Asian Economic Journal 12, 3 (1998), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8381.00060. The extrapolation to Pakistan is based on the estimated effect for Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, with all other factors affecting saving unchanged. The estimates for Indonesia would imply an even larger effect for Pakistan.

With much more savings, Pakistan would have seen more investment, faster economic growth, and a much higher standard of living today. Had the saving rate been 10 percentage points greater, investment would have been higher by 10 percentage points too, because the additional savings would have been available to lend to investors. Indeed, the impact might have been even greater because of a multiplier effect—higher saving and investment raise income, which yields more saving and, therefore, more investment. Even without such a multiplier effect, with just 10 percentage points higher investment, Pakistan’s economy would have grown by 1–1.5 percent more per year.14Assuming an initial capital to output ratio of 3, 10 percentage points more investment would have translated into 3 percent faster growth in capital. Depending on the assumed share of capital in output, this would imply 1–1.5 percent faster annual output growth. Over twenty-five years, that would have translated into a massive difference of 30–45 percent. In other words, per capita income in Pakistan today would have been close to the level of Bangladesh and India.

Intense public policy effort to achieve slower population growth and a better educated and healthier workforce would help close the income gap. With less rapid population expansion, the share of it that is of working age would rise, lifting saving, private investment, and economic growth. With adequate funding and sharp focus on family-planning education campaigns, an increase in the working-age population ratio of 5 percentage points or more within a decade is achievable, as witnessed in Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka. The experience of Bangladesh over the past half century suggests that improved education access and employment prospects for girls and women—through Grameen Bank and other microfinance institutions’ loans to women and the garment sector’s employment of women—probably also drove the slowdown in population growth. Thus, public policies and expenditure to dramatically improve Pakistanis’ access to education, especially female education, will equip the workforce with skills that enhance productivity and earning potential. Without comparable education attainment levels, it is difficult to see how the Pakistani workforce’s productivity can catch up to other South Asian workforces’ productivity levels. And, of course, supportive policies and public spending are needed to improve the health of the workforce, also without which Pakistan cannot attain the productivity and income levels of neighboring countries.

To realize these gains in living standards over the long term, steadfast implementation of sound policies and generous support from international partners will be needed over the medium term. Shifts in demographic structure are not quick, but they are indispensable for Pakistan’s long-term success. To make space for the needed public spending on education, health, and family planning—and to create a supportive environment for private investment—Pakistan must address its macroeconomic imbalances in a robust but socially sustainable way. Without liquidity support from bilateral and multilateral partners, the adjustment process will be much harder and riskier.

About the author

Aasim M. Husain is a fellow at the Consortium for Development Policy Research and a former staff member of the International Monetary Fund.

Explore the program

Through our Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, the Atlantic Council works with allies and partners in Europe and the wider Middle East to protect US interests, build peace and security, and unlock the human potential of the region.

Image: The Minar-e-Pakistan and Minaret of Badshahi Masjid Lahore are pictured. Syed Bilal Javaid via Unsplash